- Home

- Padraig Rooney

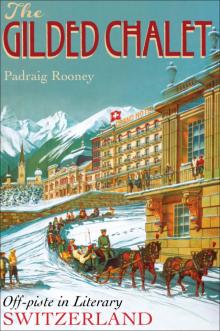

The Gilded Chalet

The Gilded Chalet Read online

Praise for

THE GILDED CHALET

“With a sharp eye for detail and a historian’s capacious knowledge, Padraig Rooney has written a superbly amusing guide to all the writers who’ve been drawn to or emerged from Switzerland. This is a book that should be stuffed into every stocking – the perfect Christmas gift!”

Edmund White, author of The Flâneur

“A fascinating look behind the scenery at how Switzerland has influenced and affected some of the greatest authors and some of my favourite books.”

Diccon Bewes, author of Swiss Watching

THE GILDED CHALET

For Y

THE GILDED CHALET

Off-Piste in Literary Switzerland

PADRAIG ROONEY

First published in the UK by

Nicholas Brealey Publishing in 2015

First published in the USA by

Nicholas Brealey Publishing in 2016

3–5 Spafield Street

Hachette Book Group

Clerkenwell, London

Market Place Center, 53 State St

EC1R 4QB, UK

Boston, MA 02109, USA

Tel: +44 (0)20 7239 0360

Tel: (617) 523 3801

Fax: +44 (0)20 7239 0370

Fax: (617) 523 3708

www.nicholasbrealey.com

www.padraigrooney.com

© Padraig Rooney 2015

The right of Padraig Rooney to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-85788-636-8

eISBN: 978-1-85788-987-1

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form, binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

Printed in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc.

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 Run Out of Town

2 Here Come the Monsters

3 The Blue Henrys

4 Going to Pot

5 The Infinity Pool

6 Keeping the Wars at Arm’s Length

7 Loony Bins and Finishing Schools

8 The Playground of Europe

9 His Master’s Voice

10 Ticino Noir

11 Truffles Missing from the Bonbon Box

12 Hard Boiled in Bern

13 On the Road

14 William Tell for Schools

15 The Emperor Moths

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Credits

INTRODUCTION

The gilded chalet opens rooms with a view to Julius Caesar, the Irish Earls, Lord Byron and me

Switzerland through the ages: Charles Addy cartoon dating from the First World War

It is perhaps only in little states that one can find the model for a perfect political administration.

Jean Rond d’Alembert

One blue June evening in 1973 I was hitchhiking across the Susten Pass in my army-surplus jacket, clogs and a wealth of hair. There was snow on the ground. A car stopped, heading north to Basel. George Harrison’s Here Comes the Sun played on the radio. My summer in Switzerland had begun. I got a job, a room, picked up some Swiss German and read Hermann Hesse and Vladimir Nabokov. As an Irishman, I learned what it means to be continental, to be a little bit Swissy, to cross my sevens and cut the butter straight. By summer’s end I had acquired an education and a beard. My first glass of champagne was above Basel’s Café Spitz. My first espresso was across the Rhine in Bachmann’s Konditorei. There were other firsts, best passed over. It was a gap summer.

The Cold War was still going strong. Earlier I’d got a lift from an American GI Joe living on a military base called Patrick Henry Village, on the edge of the Black Forest. He dropped me off outside a collection of Quonset huts, jerrybuilt bungalows and a pizzeria – a gated community, exotic to me as pizza in 1973. My next lift was from a hippy living in a commune. Nobody over forty mentioned the war. Old men clicked their heels.

Like my longhaired arty self in 1973, foreign writers fetched up in Switzerland by hook or by crook, by the seat of their pants. The poet Shelley, sixteen-year-old girlfriend Mary in tow, ran out of money on his gap summer in 1814. He got her pregnant. Two years later Lord Byron tumbled across the border in a bling Napoleonic coach, but was on the run from creditors and paparazzi. Our romantic notion of Swiss mountain landscape derives from these poets, from Byron’s ‘thousand years of snow’. Switzerland was a walk on the wild side, a view that no longer obtains.

That wet summer of 1816 has gone down in literary history. Byron, the Shelleys, Claire Clairmont, Polidori and maybe even baby William sat around the crackling fireside in the Villa Diodati. Horror literature was misbegotten. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) and the first sketch of The Vampyre (1819), penned by Byron’s doctor Polidori, are the storm’s forbidding fruit. The party came under the spell of ghoulish German folk tales. Indeed the Alp (kin to the word ‘elf’) is a mountain vampire or incubus that attacks by sitting on the sleeper and inducing nightmares – Alpträumen. Mountains the world over have inspired a folklore of otherworldly beasts: the Yeti, the abominable snowman and malevolent devils guarding the passes. The Alp drinks blood from the nipples of men and children, and sucks milk from the breasts of women. This theme of man tormented by monster is resurrected in Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf (1927), a novel begun in Basel and exploring the wolfish character of Harry Haller. The gothic-horror literary tradition is the progenitor of so much in our contemporary culture, from the New Romantics to Gay Bride of Frankenstein (2008) to Twilight (2005).

The original Romantics drew inspiration from Switzerland’s William Tell foundational myth, but it was Schiller’s mid-nineteenth-century opera about the crossbow-wielding Tell that caught the popular imagination. (Hitler banned performances of Wilhelm Tell and had it removed from the German school curriculum.) Freedom was in short supply in Russia too. Switzerland became a refuge, a beacon for nineteenth- and twentieth-century anarchists, revolutionaries and refusniks of all stripes. Fleeing the Tsarist regime, the workers of the world began uniting in the watchmaking Jura towns. It was from Zürich that Lenin’s sealed train made its way to the Finland Station and the 1917 October Revolution.

Swiss writers, on the other hand, seem to head for the borders and keep on running. In the mid-eighteenth century, Geneva-born Rousseau fell foul of that town’s tight-pursed Calvinism. They burned his books and he fled to Paris. He is Switzerland’s first world-class writer. Twentieth-century Swiss writers – Dürrenmatt and Frisch – owe their irreverence to Rousseau’s tell-it-like-it-is example, picking at the dry rot behind the Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. Likewise the travellers, the itinerants – Eberhardt, Maillart, Schwarzenbach and Bouvier – are descendants of Rousseau’s wanderlust. Writers from small countries seek elbow room and Swiss writers fight their corner in four languages. How do you negotiate a literary space different from your neighbours?

Deep in Victorian England, Switzerland was a breath of fresh air. Charles Dickens, like the Romantics before him, saw the country as an invitation to escape:

Gradually down, by zigzag roads, lying between an upward and a downward precipice, into warmer air, calmer air, a

nd softer scenery, until there lay before us, glittering like gold or silver in the thaw and sunshine, the metal-covered, red, green, yellow, domes and church spires of a Swiss town.1

And so Switzerland emerged from the cloud of history like a chalet, an Alpine refuge, an earthly paradise. A chalet was originally a small mountain cheese hut rather than the wealth and status symbol it has since become. Mark Twain in A Tramp Abroad (1880) gives us a wonderfully matter-of-fact description:

The ordinary chalet turns a broad, honest gable end to the road, and its ample roof hovers over the home in a protecting, caressing way, projecting its sheltering eaves far outward. The quaint windows are filled with little panes, and garnished with white muslin curtains, and brightened with boxes of blooming flowers. Across the front of the house, and up the spreading eaves and along the fanciful railings of the shallow porch, are elaborate carvings – wreaths, fruits, arabesques, verses from Scripture, names, dates, etc. The building is wholly of wood, reddish brown in tint, a very pleasing color. It generally has vines climbing over it. Set such a house against the fresh green of the hillside, and it looks ever so cozy and inviting and picturesque, and is a decidedly graceful addition to the landscape.2

Swiss writer Daniel de Roulet, conversely, has a historical awareness of the role of the chalet in the national psyche. His definition touches on many of the themes that run through my book: Alpine tradition stretching back to the Romans and beyond, psycho-geography, the interpenetration of foreign and local views, moneyed exclusivity and the common weal, the home of literature and myth, a refuge, maybe even a redoubt for travellers:

For us Swiss, the chalet, the Swiss chalet, as English-speakers say, is the matrix of all dwellings. From the Latin cara, which means ‘the place where one is sheltered’, I retain the earliest meaning. The poor have their thatched cottages, the rich their palaces, but the chalet is a shelter for travellers, a piece of common property; for anybody to claim it as his or her own would be unseemly. A wooden structure with a pitched roof whose ridgeline is perpendicular to the contours, this model was popularised by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in The New Heloise, reproduced ad infinitum in suburbs, plains, on the shores of lakes. Flaubert found chalets ugly, Proust made fun of them (the comfort chalet), but we Swiss learn how to draw them in childhood. It is the home of Heidi and William Tell, the immediately intelligible symbol of an Alpine tradition.3

Treatment at the Schatzalp sanatorium in Davos, setting for Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain

Switzerland was a land of milk, honey and fresh air for generations of well-to-do tubercular patients. Davos had plenty for sale; you could breathe easy. Symonds, Stevenson and Conan Doyle, those late Victorian gentlemen, saw Switzerland as a health farm, a happy valley. Pastoral imagery – cows, chocolate, cheese – as well as pristine air became desirable commodities for the crumbling industrial age. Conan Doyle may have killed off Sherlock Holmes in the Swiss mountains, but the figure of the pursuing and pursued spy-detective is alive and well and living under an alias with a numbered account.

Thomas Mann spent a thousand pages up his particular Magic Mountain (1924), in an enclave of elusive health and exclusive wealth, a brand still maximising its shareholder value. This gave rise to a literature of illness with Switzerland as panacea. As the bacillus retreated, Swiss sanatoria morphed into loony bins, clinics and finishing schools – a home away from home for wealthy sprogs and the broken in mind and body of two world wars. Hemingway and Fitzgerald both escaped into the magic mountains – from war, from the Roaring Twenties, in a search for sanity. In our time fresh air is once again on the wellness menu, with aromatherapy and lashings of liquid soap.

Besides mainstream health, back-to-nature fads at the close of the nineteenth century led wayward writers off the track to nude sunbathing and communal living at Monte Verità. They escaped the strictures of little England and a militarised Germany for little Switzerland. H.G. Wells imagined Switzerland as Shangri La, a utopian escape from the machine age. D.H. Lawrence, confined with his German wife to wartime England, recalled walking through Switzerland in Twilight in Italy (1916). Hermann Hesse, like Thomas Mann, withdrew for decades to Switzerland and became a sage on the literary and hippy trails. Their books were in my rucksack when I first came to Basel.

Male bathing area, with hip baths, at Monte Verità, 1903

My compatriot James Joyce eloped from Ireland in borrowed boots in 1904. He fled both world wars to the safety of Zürich. War too caught the fifteen-year-old Borges in Geneva, where his dad arranged for the boy to get laid. Ian Fleming was recovering from a dose of the clap. The seventeen-year-old John le Carré turned spy in Bern and polished his German. It would prove useful. For all of them Switzerland was a hideout, a refuge, the quiet good place.

Switzerland’s neutrality nurtured espionage in Geneva and Bern through both world wars. Joseph Conrad’s Under Western Eyes (1911) explores la petite Russie in Geneva during the first decade of the twentieth century. Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden (1928) plays the Great Game during the First World War, prefiguring the spy and criminal worlds of John le Carré and Ian Fleming, both Swiss educated. Le Carré’s agents, double agents and prisoners of conscience continue to see Switzerland as haven, but also as manager of the world’s slush funds. Friedrich Glauser is the daddy of the detective genre – the Krimis – in the German-speaking world. Following his example, Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s plays and detectives, and other Swiss noir practitioners, pick away at the gilt. All that glitters is not gold for espionage and detective writing in Switzerland, but often enough it hits the jackpot.

Switzerland prospered during and after the Second World War. Writing in 1952, Patricia Highsmith noticed the abundance of food and American cars in contrast to post-war deprivations across the border. Like Madame de S— in Conrad’s Under Western Eyes, we might be inclined to shout: ‘You have no idea what thieves those people are! Downright thieves!’4 An anonymous letter sent in 1758 to Rousseau cites the want of empathy in Geneva for the outside world’s travails: ‘it often sees everything in flames around it without ever feeling them; the events which agitate Europe are for it only a spectacle which it enjoys without taking part’.5 There is something of this attitude in Switzerland as a whole. What began in utopia in the first decade of the twentieth century seems to have ended in funny money by century’s end.

This view of Switzerland as a beneficiary of one if not two world wars gains currency, literally and literarily, throughout the twentieth century. Swiss and foreign writers alike take up residence in the gilded chalet. The popular view of little Switzerland on the world stage is that it did well – shiny on the outside, although ill gotten underneath. This obscures the virtues of industry, innovation and imagination that Switzerland undoubtedly possesses. But it also occludes the holier-than-thou nations, conniving banks and military-industrial complexes that have prospered from wars. Skulduggery across the field is doing rather nicely as I write. Neutral Switzerland plays it well, but the bellicose nations play hard to catch too. It is convenient to target Switzerland. Transparency has never been its strong point, except in the air.

Switzerland is partly a creation of our own guilt and desires: freedom, fresh air, money, corruption, chocolate, a winter holiday, heaven on earth. It’s the playground of Europe, far from prying eyes, where royalty go skiing, former royalty hide out, and collapsed dictators count their filthy lucre. For Swiss writers it is home, and a local home at that. The individual cantons, the narrow valley or city street, one’s Heimat – these often figure more strongly than the federation as a whole. It is surprising how cantonal – cantonné – the Swiss sense of self can be. Their literature exists on the edge of the great literatures of the age by an accident of geography and history. They might be rather tired of people dropping in, but they are also used to being on the periphery – it has its uses for the imagination.

I must belong to the last generation to have studied Caesar’s Gallic War (circa 46 bce) at school – the hearts and m

inds operation of the day. Early on, Caesar dispatches the expansionist Helvetii, tribal ancestors to the Swiss. He commandeers them as porters and begins a long tradition of Swiss mercenaries that ends with the Pontifical guards at the Vatican, in their natty Renaissance motley.

Caesar’s firm grasp of Helvetian geopolitics still holds true today:

The Helvetii are confined on every side by the nature of their situation; on one side by the Rhine, a very broad and deep river, which separates the Helvetian territory from the Germans; on a second side by the Jura, a very high mountain, which is between the Sequani and the Helvetii; on a third by the Lake of Geneva, and by the river Rhone, which separates our Province from the Helvetii. From these circumstances it resulted, that they could range less widely, and could less easily make war upon their neighbors.6

Orgetorix is the Helvetian man of the hour, but in the short term Caesar prevails. He secures the Alpine passes. Roman roads across the Alps are still there under the scrub, alongside the newer highways. Once off the beaten track, as a later emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte, discovered, you never know which way a valley will swing. The Helvetii are entrenched and wary of strangers. The Romans came and went (and did a little shopping), but Caesar is the first writer to leave his mark on Helvetia.

Coins showing Helvetian leader Orgetorix at the time of Julius Caesar’s Gallic Wars (58–50 BCE)

Basel’s Paper Mill dates from the late Middle Ages

In March 2008 I was drinking coffee in the Paper Museum down by the Rhine. The museum sits alongside a fast-running little canal called the St Alban Teich, in a district of Basel that owes its name to an eleventh-century monastery. I was back living in the city of firsts, after a gap of thirty-five years.

The Gilded Chalet

The Gilded Chalet